How They Got Here:

One hundred Russian Queens from Russia’s Pacific coast, an area called the Primorsky Territory, were brought to the

Honey Bee Breeding, Genetics, and Physiology Research Laboratory of the Agricultural Research Service (ARS) In Baton

Rouge, Louisiana. One of the geneticists responsible for this was Dr. Thomas E. Rinderer. After a three-year quarantine on

Grande Terre Island, Louisiana, the queens were moved to apiaries at the ARS lab in Baton Rouge. An additional 100

queens were brought to the U.S. each year for several more years. The ARS staff developed screening criteria that

emphasized hygienic behavior and mite resistance and then honey production, winter hardiness, and gentleness. After

extensive breeding and testing, some of the queens were transferred to a commercial beekeeper, Steven S. Bernard, and

then Charlie Harper. Pure Russian breeder queens were produced and sold on a first come first served basis. From these

breeder/production queens, Russian Queens were produced for sale to any beekeeper. Each year additional queens were

brought in, evaluated, and then moved into the general population thereby increasing the gene pool of the Russian honey

bees.

The number of Russian queen breeders has steadily expanded. Due diligence in selecting a queen supplier is still needed

when beekeepers purchase Russian queens just as you would when purchasing Carniolan or Italian queens. Two

important questions to ask are; do you have an open or closed breeding program and are the drone mothers also pure

Russian?

Queen Introduction:

Russian queen introduction can be a little difficult. Introducing a Russian Queen to a non-Russian colony is certainly

possible; it just takes a little more time and prep. It normally takes a week for a Russian Queen to be accepted by a non-

Russian colony. One can try releasing the queen in as little as 4 days, but 7 will give you the best acceptance. A Russian

colony will accept a Russian Queen in a normal amount of time. The best way to introduce a Russian Queen is in a nuc.

The smaller the hive to start with, the faster they will accept her. Introducing a queen to a nuc drops the acceptance time to

only a few days. To introducer her to a normal hive, place the queen cage where you can control the release (do not use a

candy stopper). After a week, release the queen and watch carefully. Normally the Russian Queen will quickly dive

between the frames. If she has not been accepted, the workers will usually ball her fairly quickly. If so, rescue her and put

her back in the cage. Just in case, before releasing the queen, inspect the frames for eggs to verify that there is not

another queen in the hive. Wait for 4-5 days and try to release again. Always look to see the first interactions between the

Russian Queen and the workers.

If the nuc is Russian, introducing a Russian Queen is usually faster. Put her in a cage, place her between two frames and

wait for 3-4 days and inspect. Release and observe as mentioned before. Come back and check the nuc in 4-5 days to

look for eggs and verify a successful introduction. Once successful, be ready to transfer the nuc to a deep. Russians build

up fast and even a nuc will swarm if it gets congested. The watchwords for Russian Queen introduction are; be careful,

take your time.

Spring Buildup:

Normally, Russian hives winter with a small to very small cluster. “Normal” is 3-4 frames, sometimes 2-3 frames. Your first

winter with Russians can be nerve racking. You see these “small” clusters, sometimes about the size of a grapefruit, and

become convinced that you are going to lose all of your hives.

Russians are excellent at over-wintering. They are frugal with their winter stores. Be ready for an explosive buildup. In a

2001 study of Russian honey bees, V. Kutznetzov et al. reported that the Russians are long-lived. “The last winter bees die

a month later than the Italians.” This enhances spring build-up and honey production. A strong natural pollen flow seems is

the trigger that results in extensive brood development. Conversely, nectar and/or feeding syrup will not trigger growth

without pollen. Russian build-up is similar if not faster than Italians. Do not under estimate their ability to explode in

numbers. You need to be ready with deeps and supers. If you wait too long, they will swarm. The rule of thumb is super

early and high.

Swarming:

Russians tend to swarm more than Carniolans and Italians. They start slow but when pollen and nectar become available

the queen becomes very active. The workers draw out foundation quickly and the queen fills up the frames fast. As a result

you may have up to 2,500 workers emerging each day. That is an explosion. “Beekeepers accustomed to managing Italian

honey bees will be tempted to underestimate the potential for Russian colonies to rather abruptly shift from small surviving

colonies to large colonies needing space.” Also keep in mind that Russian Queens move throughout the hive. Honey on

the top of brood frames is not a barrier to her. If she cannot find open space, the hive will swarm. And with Russians,

swarming is not delayed while the workers build swarm cells. Russians already have them in reserve.

“Just In Case” Queen Cells:

One of the most interesting traits of the Russians is their insistence on building and maintaining supercedure queen cells.

They maintain these cells all season long. Although very different from other honey bees, it is actually a good survival trait.

Should a hive lose its queen, the hive has a new queen already going as opposed to taking an egg and starting at day 1,

2, or 3. Best practice is to leave the queen cells alone, check for eggs. A queen getting ready to swarm will stop laying.

Russians will normally keep their queen cells in the upper third of the brood frame. If a queen cell is on the bottom of the

frame, treat this as a hive about to swarm. The workers will occasionally tear down and move the “just in case queen cell”.

They do not normally allow the new queen to mature unless the hive needs her.

Invisible Queens:

Russian honey bees tend to be dark. Russian Queens are also usually dark and often have striped markings. These

‘stripes’ are similar to tiger stripes, an uneven undulation across each abdomen segment. In addition several beekeepers

report that the Russian/Russian queen is dark with light blond hairs and “the longest wings of any bees I have ever worked

with”. They seem to move around the frames more than Carniolans and Italians. There have been several reports that the

Russian Queens move away from combs being worked by the beekeeper. When you inspect the hive, look for what the

Russian Queens are doing or not doing. Trying to find the queen can be a large waste of time. When doing splits, it is

usually best to separate the two deeps with a queen excluder. Come back in four days and check for eggs. Whichever

deep has eggs in it also has the queen.

Hygienic Behavior:

Hygienic behavior can have a positive impact on a colony’s ability to control Varroa destructor populations. The USDA-

ARS bee lab in Baton Rouge compared Russian colonies to other domestic lines and found that Russians expressed

strong hygienic behavior at a much higher level (69% vs 37%). In addition, it has been observed that in hives with

screened bottom boards, Russian colonies showed Varroa mites with missing appendages and bite marks. Numerous

observations of Russian bees grooming themselves and each other have been reported. In addition, beekeepers with

Russian colonies have noted how clean the bottom boards are even after the long winter months. This is all part of the

Russian bee’s hygienic behavior trait. Russian honey bees are not immune to varroa mites. They have developed a

resistance to varroa after several decades of exposure with little or no treatment while in Russia and now in the U.S. There

have been numerous studies of Russian honey bee resistance to varroa mites.

In “An Evaluation of ARS Russian Honey Bees…” Thomas Rinderer reports that:“Russian honey bees have about half the

number of varroa mites found in domestic colonies at the end of the experiment. Russian colonies, as they have in

previous experiments (Rinderer et al, 1999, 2001 a, b), reduced the growth of mite populations. The author’s conclusions

from this study state;

1.

The resistance of Russian honey bee to V. destructor strongly reduces mite populations. Use of this or another

resistant stock is central to an IPM approach to V. destructor control.

2.

Formic acid reduced mite populations

3.

Screened bottom boards did not interfere with the effectiveness of formic acid treatments.

Central to this study was their analysis, which showed that the treatment combination resulting in the lowest mite

population growth was use of Russian colonies on screened bottom boards given a formic acid treatment.

In Commercial Management of ARS Russian Honey Bees, H. Tubbs et al reports that:Varroa mite populations build up in

Russian colonies much more slowly. Also, when Russian colonies become highly infested, they will survive longer and

allow more time to treat them. Once treated, they ‘bounce back’ very nicely.

Russian hives are normally broodless from late October to January in cold climates. This helps break the varroa

reproduction cycle, and exposes the adult varroa to the Russian hygienic trait. As a result, mite loads in Russian hives are

very low through winter and going into spring. In the Washington area, queen shut-down for winter has been November

through January. Normally the Russian queen will lay and maintain small brood patches from February up to pollen flow. At

that point, she will quickly increase her laying rate.

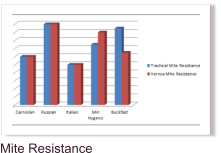

Tracheal Mite Resistance;

Russian honey bees have excellent tracheal mite resistance. In Russian Bees, Another Story, Bob Harrison reports that he

has tested his Russian bees for tracheal mites and would only find a tracheal mite in “maybe one of 30-50 samples”.

Nosema Resistance:

V. Kutznetzov et al reported that Russian honey bees seem “non-disposed for Nosema apis (Microscopy investigation

found none).

Small Hive Beetle:

There is not a lot of literature about Russian bees and the small hive beetle. One report from small hive beetle infested

Georgia states Russian bees have been observed being “very aggressive” towards hive beetle larvae. Although the bees

have difficulty grasping the adult beetle, they aggressively dug out beetle larvae from honey comb cells and removed them

from the hive. Beekeepers will need to use the same anti-hive beetle procedures for Russian bees that they would use for

any other honey bee.

Honey Production:

Initial reports (2000-2001) indicated that it was below normal when compared with other types of honey bees. The weight

of evidence now indicates that Russian honey production is as good if not better than other honey bees. In a 2003 article

titled “Commercial Management of ARS Russian Honey Bees” four major beekeepers (H. Tubbs, C. Harper, M. Bigak, and

S.J. Bernard) reported that they found Russian honey bees to be good honey producers, able to make good crops in good

years and excellent crops in excellent years. In a different report, H. Tubbs reports average yields of 130 to 150 pounds

per hive for Russian honey bees while his non-Russian bee’s yield was about 84 pounds per hive.

Queen Excluders:

One factor that may influence beekeepers that prefer to use queen excluders is that Russian honey bees seem to go

through the excluders more readily to store honey above them. This was observed by Carl Webb, a commercial beekeeper

in Georgia who has converted his operation to all Russian. He also believes the Russian honey bees make the same

amount of honey or more as other commercial bees.

Over-Wintering:

Over-wintering is one of the strongest traits the Russian honey bees have. Russian queens shut-down earlier than normal

and Russian worker population drops to winter levels sooner. Throughout the cold weather months, Russians are very

frugal. They do not consume as much winter stores as other bees. It is not uncommon to open a Russian hive in early

spring and find the cluster still in the bottom deep and the top deep’s ten frames are still full or nearly full of honey and

pollen.

One of the reason for this is the Russian winter cluster is small to very small. A typical early winter cluster is only 3-4

frames. Many Russian hives will come out of winter with only a two-frame cluster. Fewer bees, less winter store

consumption. Anecdotal reports indicate that Russian bees will not make cleansing flights unless the temperature is higher

than that at which Carniolans and Italians will fly. This results in fewer bees that leave the hive and are unable to make it

back. The fact that Russian winter bees die a month later than the Italians, resistance to tracheal mites (something

uncommon for standard commercial colonies), and non-disposed to nosema; you will have a bee that is well equipped to

withstand long hard winters (just like in the Primorsky Territory where they came from).

Russian Queen Shut-down:

Russian queens will stop laying if there is a pollen or nectar dearth. In Eastern Washington it is not uncommon to have a

pollen dearth between the dandelion bloom and the next bloom during the spring. Many Russian queens will shut down

during this short period. It is not normally a failing queen, it’s a Russian thing. Do not try to replace her; just wait to see if

she starts laying again when the pollen flow returns.

The Future:

The Russian honey bee is not a panacea. It is a very hardy and hygienic bee with numerous traits both good and not so

good. Unless a new beekeeper attends a Russian honey bee oriented beginner’s class, it is not recommended to start out

with Russians. The management techniques are just different enough to cause significant problems.

The Russian Honeybee Breeders Association has been formed to maintain the current pure Russian queen lines and

expand the gene pool of association members. Each member of the RHBA maintains two lines of Russian queens. Each

year they evaluate, select, and produce 36 queens from each line and then send two of each line to the other 17 members.

The 34 queens received from the other members are used as drone mothers and produce additional drone mothers. The

drones increased each member’s gene pool each year. New queens are grafted from the line breeder queens and moved

to mating yards near drone mother yards. After successful mating, the new queens are established and then evaluated for

possible selection as breeder queens for the next year. The cycle then repeats.

Introduction:

What is the Russian Honeybee? First off, it is not an Italian or a Carniolan, but it does have several of their

characteristics. Genetically, a Russian honey bee is Caucasian with some Italian and Carniolan lineage. They are a dark

bee with black abdomens with grey hair. Although they share some Carniolan and Italian characteristics, they definitely

have their own “Russian” characteristics.

The Russian honey bee refers to honey bees (Apis Mellifera) that originate in the Primorsky Krai region of Russia. This

strain of bee was imported into the United States in 1997 by the USDA’s Honeybee Breeding, Genetics & Physiology

Laboratory in Baton Rouge, Louisiana in response to severe declines in bee populations caused by infestations of

parasitic mites.

Why Russians? Some of the earliest frustrations as a new beekeeper is winter losses and having to treat for tracheal

mites or verroa mites. The Russians are extremely adept at dealing with both of these issues as their species has

survived through them for hundreds of years. Typically Russians run a little higher in price for a queen, but when one

considers the savings of chemical treatments and better survivability; they are a great value. Additionally, their prices

have declined in recent years and can be bought for the about the same price as Italians or Carniolans. The sources are

still more limited so getting an order in early is essential.

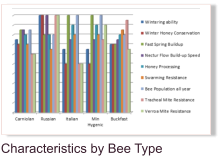

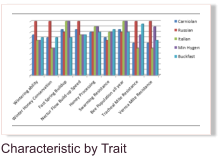

Characteristics and Comparison Charts:

**Note** the charts below are derived from a combinations of studies and comparisons. They are not a study that this

company has performed. A single study from a major laboratory or university comparing all of these lines has not come

to light thus far. If information presented in these charts differs from your own experience, please do not write to request

us to correct our information unless you are a major university or laboratory who has performed a similar study.

The Primorsky Honeybee